Enter the Snakepit - December, 2011

J. G. Pasterjak, Grassroots Motorsports

[This article originally appeared in the December, 2011 issue of the Grassroots Motorsports magazine.]

http://cindilux.com/media-link-articles/473-enter-the-snakepit#sigProIdc845077d9a

As I looked a little deeper into the proceedings, I realized that this wasn’t a mere press outing where they’d shuffle a bunch of journalists through the cars, then treat them to lunch and a Powerpoint presentation. Nope. I’d be driving the Viper at a NARRA-sanctioned weekend on a hot track.

No, wait a minute here. I’d be racing the Viper ACR-X against a snarling field of other ACR-Xs in this season’s inaugural Dodge Viper Cup event. What had begun in my mind as a pleasant diversion in a fast car suddenly became a bit of an intimidating, rapidly approaching milestone.

It got all too real when I saw the Viper—my Viper, designated by my correctly spelled name spanning the bottom of the windshield—roll off the Lux Performance transporter. Whatever happened to this car during the weekend, I’d get blamed for it, if only because “Pasterjak” was now affixed to the glass in high-contrast vinyl.

After arriving Thursday, getting roughly fitted in the car, and setting up our Grassroots Motorsports tent next to the Lux trailer, I adjourned to the comfort of the Chateau Elan to think a bit more about what I had gotten myself into.

Here were the facts as I saw them. It’s not exactly like I’m a rookie or something. I’ve been road racing for more than two decades and in a variety of cars (although, I admit, usually in underpowered “momentum” race cars).

In those two decades I’ve run some close races, shown that I can be competitive in many different venues, provided competent feedback to the crews I’ve been associated with, brought home a little trophy hardware from time to time and, most importantly, brought home the car every single time.

I was probably the definition of a journalist gentleman racer: fast enough to compete and stay out of trouble, calm enough to deliver someone else’s machinery back to its rightful owner, and savvy enough to realize that—at the end of the day—I’m there to write a story, not audition to be the next World Challenge superstar.

This was different, though. I had sat in that Viper. I had looked at all 8.4 liters of its 640-horsepower V10 engine lurking menacingly under that impossibly long hood. I had seen the Michelin slicks, so wide that their only purpose on this earth was to commit a hate crime against physics. I felt it: the presence. They were about to strap me into an X-wing when all I’d ever done was bull’s-eye womp rats in my T-16 back home.

While that may be enough background for some cocky recruits, I have to admit I was a little nervous—not just because of the machinery, but because of the responsibility. With a base price just north of $125,000, the Viper ACR-X starts $7000 higher than what I paid for my house. (Sure, we got in before the bubble swelled and got a good deal, but still.…)

http://cindilux.com/media-link-articles/473-enter-the-snakepit#sigProId5701626154

Then I saw the post from Duke on our message board, responding in a thread where I had posted some quick pics of the upcoming weekend’s activities. Paraphrasing his reply, he said that stuff like this is what makes all those late nights and long weekends of working on the less glamorous end of magazine production all worthwhile.

You know, it kind of does. But in a way, that makes it all the more intimidating.

At Your Service

The reason this stuff can be intimidating is that, while I have a very competitive spirit, I just don’t have any sort of killer instinct. I appreciate the journey, regardless of the result. So when good things happen to me (like the opportunity to drive a fire-breathing race car at one of my favorite tracks in the history of ever), I figure that somehow I am undeserving.

But Duke came along and put everything in perspective.

Yeah, okay, I admit it: This job has perks. And they’re pretty cool perks at that. But a lot of jobs have perks, and a lot of folks probably take for granted things I’d love to experience. My wife—a third-grade teacher—recently got an email from one of the kids she taught during her first year on the job; that “kid” had just graduated college. A friend recently celebrated the 60th birthday of one of her co-workers. Oh, did I mention that co-worker is also a dolphin?

Me, I’m envious of stuff like that. But then I slid into that RaceTech seat in the Viper ACR-X, and suddenly I couldn’t care less about college graduates, dolphins, or much of anything else.

But the bottom line, of course, was that the purpose of my being there and participating in this event was to relay my experience to you. That’s really the whole point of the magazine business, I suppose. We act as conduits between the readers and a world they may not have access to in hopes of using our connections to enhance their knowledge.

So really, all of us were in that Viper together (I’m sorry I farted that one time). I promise to do my best to relay the experience to you, but I’ll also warn you going in that the intensity of the experience may in some cases exceed my abilities to properly convey it. In the words of Jodie Foster’s character in the movie “Contact,” “They should have sent a poet.”

Fall Into the Snake Pit

First off, there’s something cool about seeing your name on a race car—any race car.

When your name is plastered on the windshield, you’re no longer just a helmet and gloves behind a window net. Suddenly you have an identity and a feeling of responsibility for the machinery. If car No. 53 did something stupid, it would be clear who the culprit was, and it’s not like there were a whole bunch more Pasterjaks for me to try and pin the blame on.

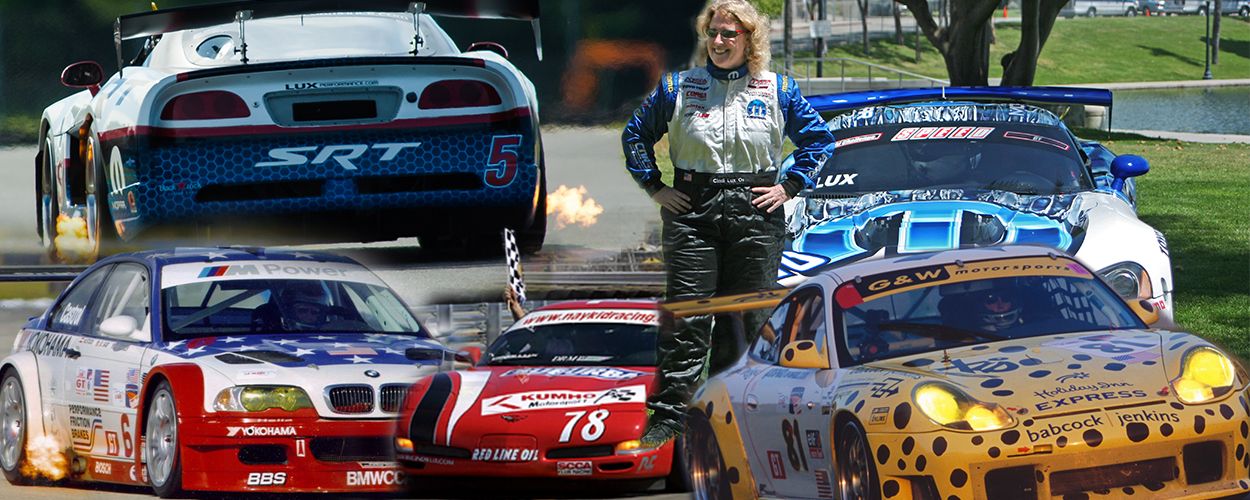

Luckily, I had a good support structure. Lux Performance, headed by pro racer Cindi Lux and her husband, mad genius engineer Fred Lux, is an absolute class-act organization.

And I’m not just being glib when I refer to Fred as a mad genius. This is a guy who outfitted a Rascal scooter with an electric motor that could lift an elevator and called it a “pit bike,” even though its well-worn wheelie bars hint at far more sinister uses. When he’s not building or perfecting race cars, he builds robots that kill for shows like “BattleBots” and robots that save lives (and probably also kill) for the Department of Defense.

Corey Piazzese, my crew chief, was repeatedly driven mad by the fact that I never got into the car early enough. In my defense, it was hot enough to melt lead, but it’s also a habit of mine to delay getting into the driver’s seat. Just sitting there doing nothing except watching other people work gets me wound up a bit. I feel like I’m not contributing.

But I quickly figured out that this was a whole other level of racing. NARRA and the Dodge Viper Cup may have their roots in the club scene, but this is very much a pro series with sponsorship, TV coverage and prize money. My job was to be in the damn car early. That was how I was contributing. The last thing these professionals needed was me running around screaming, “I’m helping! I’m helping!” and getting in everyone’s way. My job was to drive.

And, honestly, despite the Viper ACR-X’s epic stats, that part of the job was not so hard. Before my first practice session, Cindi had described the Viper’s demeanor as similar to “a big MX-5 Cup car. You don’t muscle it. If you do, you’ll just go slower. You have to finesse it a bit and drive it neat and tidy.”

She was right on the money. The ACR-X is a willing partner and, dare I say it, surprisingly benign. That’s not an adjective you’d normally ascribe to a 640-horsepower car with slicks so wide that the tread faces have several different zip codes, but it’s true.

With a light touch, the car hustled around with little drama. That was due in part to the fantastic aero package, which added a ton of stability in the high-speed stuff—over 1000 pounds at 120 mph, to be exact. If I tried to hammer the Viper or slide it around, it didn’t bite too bad, but I wasn’t going to go any faster. The steering was a little on the light side and didn’t provide much feedback. That turned out to be okay, though, since it was enough of an exercise just leveraging myself against the considerable g-loads the car could produce.

http://cindilux.com/media-link-articles/473-enter-the-snakepit#sigProIdc9f7712e87

Speaking of confidence, the one system that didn’t punish brutishness was the brakes. Jump on them as hard as you like, and the car just stops.

The pedal may have felt a bit different as the temperatures rose, but that immense declarative force was always available. And I’m not just talking about the huge-calipers-plus-sticky-rubber kind of good brakes. I’m talking about the kind of brakes you can only get when you have huge calipers, sticky rubber, and a perfectly balanced chassis that maximizes the grip of each tire in every axis. I’m talking about the kind of brakes that would make Colonel Stapp say, “Damn, this thing stops fast.”

With so much horsepower on tap, you’d expect the car’s forward thrust to be its most dramatic dynamic element. Thanks to its linear power curve, the 8.4-liter V10 felt downright civilized compared to those immensely forceful brakes.

Into the Deep End

My first excursion onto the track was an object lesson in humility. And before you skip ahead to see where I balled it up, I'll tell you I did no such thing.

Within half a lap, I realized something. While I completely understood that I was nowhere near the limits of the car, it became clear that after a couple sessions I’d be turning reasonable—if not competitive—lap times.

I’d love to say that this was due to an immense amount of skill and personal charisma on my part, not to mention comically large genitals, but that’s not really the truth. I’ll admit to having a moderate amount of skill and confidence behind the wheel, but the true star here was the Viper ACR-X. As promised, it drove “small” and was exceptionally easy to place.

That last attribute was especially beneficial, since during these practice sessions we were on track with nearly 70 cars of wildly varying types and capabilities. Even though I wasn’t up to speed in the Viper, I could easily and confidently slice through slower traffic (and by “slower traffic,” I mean nearly every other car on track) as though I had been driving the car for years. And those intense, progressive grip characteristics meant I could drive by slower cars on the outsides of corners without having to worry much about proper line.

No, the intimidating part was not the car, but rather the fact that I just didn’t know if I would be up to communicating how accessible it made these levels of performance. Normal adjectives do not do justice to the way this car surgically amplifies any natural talent the driver may have. They also fall far short of describing the overwhelming sense of confidence that comes with the feeling that you aren’t fighting the car for control, but working with it toward a common aim.

By the second session, the speed began to come, and another reality set in: The same track can look very different in two different cars. The last time I’d driven Sebring, it was in our MINI Cooper S project car. That car was also blessed with a prodigious amount of lateral grip from its fat, sticky tires, and it hustled through the turns at Sebring with a great deal of poise.

http://cindilux.com/media-link-articles/473-enter-the-snakepit#sigProIde28b662cca

Case in point: I negotiated Turn 1 at probably 80 to 85 mph in the MINI and 90 to 95 mph in the Viper. However, where I was dabbing the brakes in the MINI at corner entry to slow it from maybe 95 mph, I was rocketing the Viper toward Turn 1 at over 140 mph.

In the MINI, I was accustomed to navigating Turn 1 with a lift and a brush of the brakes. In the Viper, the turn had suddenly transformed into a hard braking zone from purely ludicrous speeds. A quicker machine can really change the shape of a circuit you’ve gotten used to driving a certain way.

I had come to know Sebring as a track that required patience and deft moves to negotiate the wide-open spaces and flowing corners. The Viper’s sheer warp speed changed all that, making Sebring seem smaller than I remembered. Curved straights were now corners. Long straights that once gave me time to ease my grip, tighten my belts, and check my email on my smartphone suddenly provided barely enough space to reposition the car for the next braking and turn-in zone. That type of speed required a serious recalibration of my internal rhythm, but I realized that once I put my brain on fast-forward, the racing line was still the racing line, even if it was going by at twice the speed.

My confidence level was high after just a few miles thanks to the predictable nature of the car, and after a couple of sessions my speed even began to build to the point where I was feeling pretty good about things.

Then I found out about the standing start.

Gas and Go

Few scenes can match the intensity of a standing start in a road race. Snarling mechanical monsters fight with the pavement for traction while simultaneously battling each other for position. And while I’d enjoyed several standing starts in various series as a spectator, my reaction was always one of stunned amusement. I was thrilled to bear witness to such a spectacle, but equally glad I was watching from a place of relative safety.

Well, Dodge Viper Cup racers are required to put on their big-boy pants, pull up to the line and unleash all those horses in a war for Turn 1. Simply accelerating a car that powerful from a dead stop would require a bit of skill, but the thought of doing it alongside a dozen similar machines at the same time sent my testicles north faster than a retired Canadian in April.

Of course, we’d get to “practice,” which consisted of pulling our machines into a designated area in the hot pits during a practice session and finding that magical point where the clutch turned thoughts into realities.

Fred Lux guided me through my practice launch from the other end of the in-car radio: “Push the clutch in, put it in first, bring the revs up a little, and when you’re ready to go, let out the clutch then short shift into second and stand on it.”

Gee, Fred, thanks for the complex discussion on the physics of acceleration.

Sarcasm aside, it really was pretty much that simple. The obscene grip afforded by the slicks meant that I really could get deep into the throttle without breaking the rear end loose. The key was to simply walk the car out of the hole, then roll into the gas.

If I shifted into second prematurely, no worries. Nearly 600 lb.-ft. of torque would still pull me away smartly. My biggest fears were either getting off the clutch too slowly and overwhelming it, or getting off too quickly and stalling the car. Oh, and there was also the matter of the several other Vipers surrounding me, all howling at the top of their V10 lungs.

But, for now, I had successfully gotten the car rolling from a standing start with a moderate amount of aggression. The pants-crappingly terrifying concept of a standing start was now downgraded to merely unsettling.

And then it started to rain.

Saturday and Sunday would each feature a race, preceded by a qualifying session and a practice session. By the time our first qualifying session rolled around, we were in a full-on-Florida spotty thunderstorm pattern. The rain would come and go, interspersed with enough sunshine to completely dry the racing line.

When we went out to qualify on rain tires, we made the right decision. When the huge accident occurred during the opening lap of qualifying, I was mercifully not part of the carnage, but the crash shut down the proceedings until the session time had basically expired, rendering tire choice somewhat moot. Because of the troubles during qualifying, we were gridded for race No. 1 by practice times. That meant I’d start mid-pack.

Although the qualifying session was cut short, one thing that was painfully clear was how incredibly slippery Sebring’s painted start/finish line can be once it’s topped with just a little bit of moisture. Rolling over it in fourth gear with any positive throttle produced wheelspin, which is a bit of a sphincter-tightener when you’re rocketing between two concrete walls at more than 110 mph.

The rain continued to fall as race time drew near, and we learned that the standing start would be abandoned in favor of a far safer rolling start. As it turned out, the change didn’t really matter.

When the green flag flew, torque overcame traction and chaos ensued. From my mid-pack starting position, I briefly saw the yellow car of Dave Fiorelli move in toward my passenger-side mirror. I glanced forward for a second, then back to the mirror, and the yellow car was gone.

In that blink of an eye, Dave had broken traction, slid across the track, and nosed into the wall so hard that race control brought the entire field into the pits while the track was repaired.

Suddenly, the element of danger became very real. These massively powerful, 3000-pound concoctions of steel, plastic, glass and rubber seemed like brutal weapons as we watched a forklift reposition the concrete barriers. When the race finally resumed—well after our allotted time limit had expired—the field ran a single lap under green-flag conditions. The few cars that had chosen slicks over rain tires ran away on the now-drying track, and the rest of the field seemed to decide that it would be better to live to fight another day.

Another Day

This fact was becoming clear during the course of the weekend: The Dodge Viper Cup and the NARRA group that sanctions it are made up of some serious players. While the racing is clean and fair, this is not a touring club or a bunch of rich guys out playing race car driver.

Yes, there are a bunch of rich guys but, like the racing itself, there’s a general blue-collar toughness among the competitors. The typical NARRA or Dodge Viper Cup pilot seems to be someone who built a company with their own two hands, sweating and scrabbling every inch of the way until they achieved success, and the racing reflects that spirit with alarming accuracy.

Me? I’m just a guy who’s written a few mildly amusing stories containing sketchy metaphors and thinly veiled boner jokes. To say I was out of my league would be an understatement.

Take NARRA President Tom Antonelli, for example. He owns a trucking company in Chicago. He could probably snap his fingers just once and make my wife a widow. He’s also got a thousand-yard stare that seems to say, “If you see my Viper Comp Coupe in your mirrors, that next corner is mine.”

It was more of the same in the Dodge Viper Cup. Just driving a Dodge Viper doesn’t mean you can intimidate your competition out of the way by filling their mirrors and asserting yourself. After all, the guys you’re trying to scare are in Vipers, too, and they’re exactly as scary as yours. In spec series in general, drivers must fight for position with overt, dramatic moves, and in the Dodge Viper Cup, those moves happen at ridiculous speeds.

So as we approached the final race of the weekend, I realized that I wasn’t going to barge onto the scene with my moderate pool of talent and big-dog anyone out of a top finish. When I rolled up to the line for the standing start—Sunday’s race would have dry and ideal conditions for a sports car race—it was clear that I was in the middle of a very serious field, and simply being competitive would be enough of a challenge.

Qualifying had been a bit of a wash, literally and figuratively. It was raining when the green flew, but the sun quickly broke and the track began to dry. Some teams had guessed correctly and went out on slicks, while a few lucky others dove into the pits at the right time.

Both of the Lux Performance cars made the decision to go out on rain tires, which seemed like the absolute right decision on the initially wet track. Despite its prodigious power and torque, the ACR-X was balanced and predictable in the wet as long as I kept the throttle under control. Some of the 120-plus-mph kinks on the back section of Sebring were a bit pucker-inducing, but so long as I kept a tidy line I felt safe and secure.

Our car managed to be one of the faster ones on wets, so we earned an eighth-place starting spot. My Lux teammate, Frank Lussier (who campaigns his own Viper road race car but was doing time in the other Lux-prepped ACR-X this weekend), was able to dive in for slicks during qualifying and was right ahead of me in the sixth spot.

So right off the bat, the stage was set for disaster, as both Lux cars were parked nose to tail in the middle of more than a dozen other hissing snakes. Before we strapped in for the final race of the weekend, Cindi looked at us with an expression that was both very serious and calming.

“I want you guys to relax, have fun, drive aggressively but not recklessly, and whatever you do, don’t hit each other.” She said it with a smile, but it was a smile that made it clear she’d cut us from ear to ear with the box cutter she keeps in her shoe if she had to prove her point.

Actually, I’m not sure she keeps a box cutter—or any other type of blade—on her person for just such an occasion. But I figured that image would help me aim for some playing children instead of the other team car when I inevitably lost control. I’d rather face their grieving parents than the Luxes, who had been so generous and professional all weekend. I was already feeling guilty enough for eating all their Twizzlers.

Go Time

And here’s where I completely run out of writing skills. There’s really no way I can accurately describe the intensity of a standing start in the middle of a pack of 640-horsepower race cars.

As I rolled into my grid spot and the marshal lined me up, there was almost nothing I wanted to do more than make some smartass remark to my passenger to break the tension. Then I looked over and realized that I was all alone in this metal missile with my name printed in 6-inch-high letters on the windshield.

I also realized that getting on the radio and saying to the crew, “OH MY GOD, YOU GUYS, I’M SO EXCITED I THINK I MIGHT PEE. OH WAIT, I JUST DID A LITTLE. HAHA LOL!” would probably not fill them with a sense of confidence that they’d ever see their $125,000 race car again.

After that, it was time to watch for the 30-second board. The appearance of the 30-second board doesn’t necessarily mean that you have 30 seconds until the race begins; it just means that sometime in the next 30 seconds, the starting lights will illuminate, then shut off to signal, “Go!”

What it means in actual practice is this: The 30-second board is up. Put the clutch to the floor and slide it into first gear. Make sure to get that clutch all the way to the floor. Yeah, it has a bit of a high engagement point, but any movement of the car before the start—and I mean even the slightest twitch—will incur a penalty of at least a stop-and-go. Don’t screw this up, Pasterjak.

Clutch in. First gear. Make sure it’s first. Take the lever out and slide it back in. Was it all the way to the stop on the left? Yeah. Is it all the way to the stop forward? Yeah. First gear.

Remember to breathe. Put your game face on.

Start lights just came on. One car twitched. There went another one. Heh, I may have already beaten someone.

Lights out.

Left foot up, right foot down.

I’ll spare you any more time in my head and tell you what happened next. About the time I got my clutch foot all the way off the floor, I realized that the car in front of me—my teammate—was not moving. Then came one of my great personal triumphs of composure: I kept my foot in it, shifted smartly to second, eased my car to the left and began to drive through the rows of cars, gaining two or three spots in the process.

Although I feel terrible—but not too bad, which I’ll explain in a minute—for Frank for stalling out, it was probably the best thing that could have happened for me at that moment. Otherwise, I would’ve been rocketing toward Turn 1 still waiting for “the scary thing” to happen, knowing that at any moment the universe would realize that I was in way over my head and summarily punish me for daring to fly too close to the sun.

But the scary thing happened the moment the race started, and I dealt with it calmly and with a poise that I wasn’t quite sure I had. If I could deal with the Mongolian clusterbang that is a standing start in the Dodge Viper Cup—complete with the guy in front of me killing it—I’d be fine.

Unfortunately, any goodwill I gained from the universe with my start was collected by Turn 2. A crash in Turn 1 brought out a full-course caution for the next lap or so. (By the way, I was passed a couple times during that full-course caution. I’m not naming names because I’m a good guy, but I totally know who you are.)

By the time we went green again, the field had bunched up and my good start was suddenly irrelevant. The next dozen laps were among my most enjoyable in any race car ever. While most of the field spread out, I ran in a three-car pack that was fighting over the sixth, seventh and eighth spots for most of the race. I was the meat in a sandwich formed by the Larry Carter and Frank, my teammate.

I’m sure seeing both their cars running nose to tail gave the crew a few sweats, but Cindi Lux was constantly on the radio with words of encouragement. Although Cindi is an accomplished racer herself—a 12-time road racing champion, actually—she’s also a supremely capable coach, which is a skill set in its own right. She was always on the radio with the right words at the right time. Tighten your belts. Loosen your hands. Move your eyes. Breathe. Relax. Have fun.

She didn’t have to tell me that last thing. Still, I appreciated it, even though I still had some pangs of guilt for destroying her bag of Twizzlers and a tub of perfectly salted mixed nuts.

Although our little three-car battle never saw a pass during the race, that doesn’t mean there wasn’t action. Someone would move over 12 inches to take a look, the car ahead would move over 8 inches to assert its position. Someone would brake a little early, the other cars would run a little wide to try and get better acceleration off the corner. It was huge cars playing cat and mouse with tiny moves, and it was exceptionally fun.

It became apparent, though, that to make a pass, someone would have to make a big move. Such is the nature of spec racing. Either that, or someone would have to be in the right place at the right time when someone else made a mistake.

I made that mistake in the final turn of the final lap. A tiny bobble in Turn 17 allowed Frank to get his nose inside me for a drag race to the finish line. It was a race he won by about 3 feet. When we crossed the line, my car’s nose was about even with his car’s front hub.

Of course, there’s no provision in the results for close finishes. The difference between eighth and ninth place may have only been a yard, but until someone comes up with an eighth-and-a-half-place award, it doesn’t really matter.

The Point?

What have I taken away from all this? Besides learning that every once in a while, some lucky, undeserving bastard gets to drive a Viper, I can confidently state the following:

Dodge has built a truly superior race car with the ACR-X. For me—a guy who usually puts his butt in cars with 120 horsepower—to be able to hop in a car like this and compete with guys who do it every weekend is remarkable. In Sunday’s race, I ended up in ninth place, but my fastest race lap ranked fourth in the field. Yes, I have some small degree of skill, but Dodge deserves the real credit for building a car that can be successfully wrangled by a layman.

An equal amount of credit must also go to Lux Performance. Make no mistake, they are a pro race team. But that doesn’t mean they always have sticks up their bums. They understand that while racing is a business, it’s still supposed to be fun—and even a fun pursuit can be approached with high standards.

Ultimately, I hope what came across was some sense of what it was like to experience this ultimate ride. I’m humbled by the opportunities I’m given from time to time, but I realize that my mission is to give you some idea of what I was lucky enough to stumble into one weekend. If I’m ever invited back, maybe some of you can join me.

http://cindilux.com/media-link-articles/473-enter-the-snakepit#sigProIde085f2073b