[Oregonian] NBC's "Today" honors Cindi Lux

THE OREGONIAN

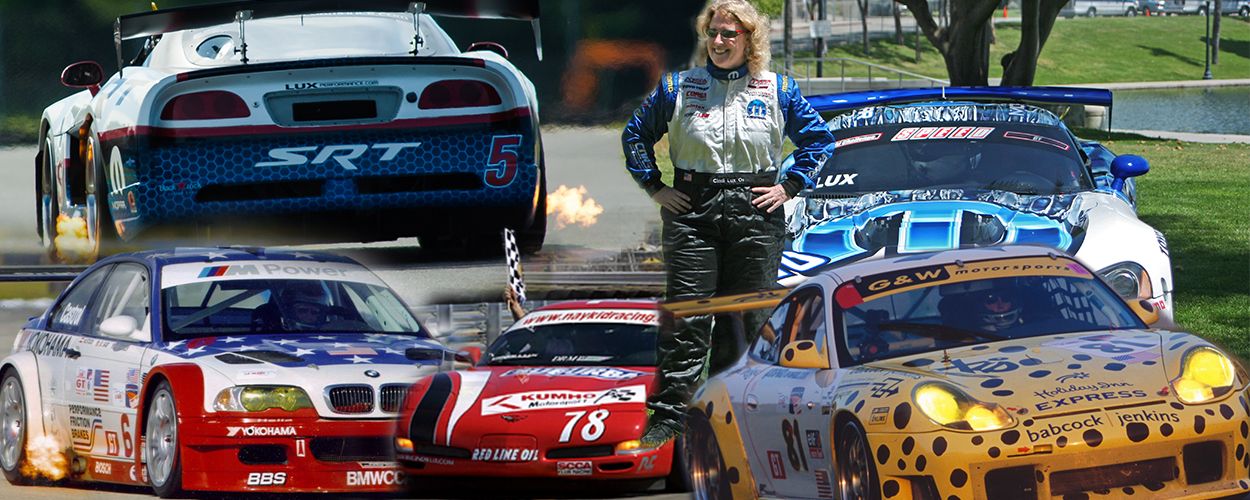

A PACE-SETTER FOR WOMEN

Date: Friday, May 7, 2004

Section: NORTHWEST

Edition: NORTHWEST FINAL

Page: B02 MICHELLE MANDEL - The Oregonian

Illustration: 2 photos by JUNE BOONE/for The Oregonian

Dateline: ALOHA

Summary: NBC's "Today" honors Cindi Lux of Aloha, for her dominance in a sport dictated by men

Cindi Lux laughs, telling how NBC's "Today" show called, asking if she'd come to New York for a multiday makeover set to air today.

Lux, who's made an international name for herself racing cars, wondered if producers had the right woman. "I work very hard at not being a tomboy," she says.

Oh, no, producers said. The segment, they told her, was a "celebration for folks who have careers out of the normal box. Who sacrifice personal lives to be on the road."

Lux still doesn't quite get it. But she decided if NBC wants to fly her and her husband, Fred, to New York and give her a new hairdo and clothing -- well, hey, she says with a grin, she's not going to say no.

"It could be fun," says Lux, who wears a lime-green Falconable dress shirt, navy blue blazer and jeans. Her wavy shoulder-length blond hair frames her face. Pink polish shades her fingernails.

"I just don't want to look stupid," she says.

That wouldn't do. The 42-year-old Aloha resident is among an elite group of women worldwide showing men they can kick rear end on a racetrack. Most of her 60 career wins, in fact, have been against men.

But Lux is a rising star in a sport where money, not necessarily talent, makes or breaks careers. She knows she must always try harder and be better, both to gain sponsorships and to break ground for women race drivers in general.

"Cindi is one of the most fierce competitive people that I know," says Joe Harlan of Oregon City, who has raced since 1988, many times against Lux.

"She has a desire and a drive to race cars that very few people in the sport possess," he says. "It doesn't matter that she's a woman. If she had the money, she could take it all the way to the top.

"She could be the best."

How Lux transformed herself from the daughter of a car salesman into a world-class driver is testament to her own deep-rooted sense of competition. From her earliest years, growing up in Yakima, she wanted to win. An avid athlete, she downhill skied and earned a brown belt in karate. She also competed on Arabian horses.

"My mother was a very strong woman who very adamantly believed in a diversity of sports," says Lux, who has memories of riding a Suzuki 50 minibike after her two older brothers on motorcycles. Their rule: If she couldn't keep up, she couldn't come.

"My parents also taught me that there's no free ride," she says. "If I wanted horses, I was the one who had to be up at 5 a.m. feeding them. I learned I could have whatever I set my heart on if I worked hard enough."

Her grandfather, Carl Hahn, raced cars in the 1920s, and her father, Dick, raced his Ferrari to victory in Portland's first Rose Cup Race in 1961 before hanging up his helmet to raise his children.

But Lux never dreamed of racing cars. In 1985, after graduating with a business degree from the University of Puget Sound, she refocused her competitiveness on career, working for Toyota in California.

"I started out in the parts department, responsible for hundreds of millions of dollars' worth of inventory," she says, "and moved up in the ranks of Toyota, ending up working in developing products."

Lux thought her future was set. Then in 1987 she went to the Long Beach Grand Prix in California.

And everything changed.

"I watched the cars and I thought, 'This doesn't look very difficult,' " Lux says.

Lux soon learned the sport's no cinch. Within weeks, Lux paid $2,300 for a four-day class in the basics. She loved the experience, she says, although she was scared at first.

"I thought you just floored it and drove like gangbusters," she says. "But that's not what it is at all. You have to tell the car what to do, to figure it out. I loved the challenge."

Soon she bought her own race car, a Dodge Shelby Charger, which she says "was a piece of junk I paid too much money for." No matter. She started winning amateur races, earning both trophies and respect. In 1990, Mitsubishi asked her to pilot one of its amateur race cars.

That's when Lux learned the humbling (and dangerous) aspects of her sport. A tire went flat, spun her off the track and kicked up so much dirt that another driver couldn't see and veered off the track.

T-boning Lux.

Fortunately for Lux, she wasn't hurt, and her future husband, Fred, who worked for Mitsubishi's race team, performed miracles with the car. In 1991, Mitsubishi asked her to pilot a pro car.

Lux says her learning curve went vertical, as she soaked up everything she could learn from her two male teammates. Within a year, she was beating them consistently.

"She's not satisfied until she does her absolute best," says teammate Scotty B. White, 45, owner of NayKid Racing in Puyallup, Wash. He and Lux drive 405-horsepower Corvette Z06s up to 170 mph in Sports Car Club of America amateur competitions nationwide.

"Some guys talk up a race beforehand, but not Cindi," he says. "She just smiles and is pleasant to be around, until she gets in a race car."

Just when racing seemed her destiny, Lux's mother and best buddy, Jackie Snyder, was diagnosed with cancer, and the daughter wanted to be closer to home. In 1992 Lux transferred to Portland, focused on her Toyota career and eased off racing.

Two years later, she quit Toyota and started her business, Lux Performance Group, which provides most of her income. Car manufacturers hire Lux to test-drive new cars and to explain those cars to dealers worldwide.

Lux still longed to race. She just couldn't afford it. The Corvette she now races costs $75,000, not including what it takes to keep it running. And that's cheap. When she competed in Georgia's Petit Le Mans, she drove a car worth $250,000 -- heady, she says, considering it could crash in a split second.

It wasn't until the Women's Global GT Series in 1999 that Lux really got back into driving. Lyn St. James, the second woman to compete in the Indianapolis 500, invited her to try out for an all-women racing series among 75 of the world's best drivers.

Lux tried out, drove the fastest single lap and then won the series.

Since then, Lux has slowed only when money's tight. That part of the business bums her, because it brakes not only her progress, but also that of women drivers in general.

"Things are just starting to open up to women," says Lux, who still fields occasional snide comments from men drivers. "It's tough to say I'm waving the woman's flag, but people say what I'm doing on the track is important for future female race-car drivers.

"I need to win races to make strides."

Michelle Mandel

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

All content © THE OREGONIAN, reprinted with permission.